With the first Solvay Conference for Biology, the International Solvay Institutes are continuing a major and important scientific tradition

On 15 June 1911, 20 leading physicists received an “invitation to an International Scientific Conference to clarify current questions of molecular and kinetic theory”. The invitation was confidential and signed “E. Solvay”. The conference that took place in Brussels from 30 October to 3 November 1911 is today considered the first international conference on physics, and its significance in the progress of science is recognised worldwide. A second committee began organising the Solvay Conferences on Chemistry in 1922, after the First World War. This year, the first Solvay Conference for Biology will take place from 18-20 April, culminating in a public event at Flagey on 21 April.

“The idea of an International Scientific Conference was established in 1910 by Walther Nernst, the director of the Institute for Physical Chemistry at Berlin University,” says VUB postdoc Alessio Rocci. Rocci works with the Solvay Archive, kept at ULB, under the guidance of VUB rector and physicist Prof Jan Danckaert. “The timing of the plan turned out to be crucial. Ten years had passed since Planck had postulated the elementary quanta to explain the radiation emitted by objects when they are heated. Later, Planck’s hypothesis was able to explain a number of other physical phenomena.”

Ernest Solvay was an industrialist, as well as an inventor, philanthropist and the founder of the research institutes for physics and chemistry that today bear his name. “But Solvay was much more than a patron of science,” says Rocci. “Driven by passion, he was dedicated to scientific research. He summarised his research at the time by highlighting three directions and three problems, which in his view constituted just one. According to Solvay, there was one problem in physics: what are materials, space and time? There was one problem with knowledge of physiology: how does the mechanism of life work, from its humblest manifestation to the phenomena of human thought? He also believed there was another problem, complementary to the first two: the evolution of the individual in a social context.”

Walter Nernst found fertile ground when he proposed to Solvay that they bring together a small, select group of leading scientists for the first Conference of Physics in 1911. At the same time, the chemist Wilhelm Ostwald presented Solvay with a proposal for an International Institute for Chemistry.

Nernst’s idea was the most effective, and Henri Poincaré was among those inspired by the discussions at the first Conference of Physics. “For Solvay, the true revelation was meeting the president, Hendrik A Lorentz from Leiden, the great master of theoretical physics, who led the debates and was admired and respected by all,” says Rocci. “Here was a man who could help with implementing a plan that was close to the industrialist’s heart: awarding research grants to scientists from around the world and organising recurrent Conferences for Physics and Chemistry.”

The cooperation between Solvay and Lorentz led to the creation of the International Solvay Institute for Physics in May 1912. “Our current understanding of the history of Solvay’s project and his developments is that the discussions at the conferences accelerated the knowledge process around quantum physics. By awarding grants to international laboratories, he enabled quantum theory to be developed further.”

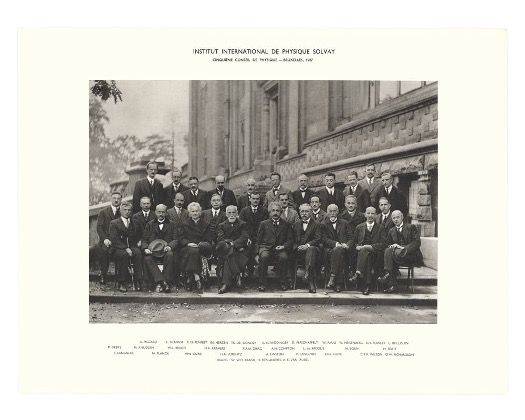

According to Nobel Prize winner Werner Heisenberg, that process ended in 1927 with the final year of Lorentz’s presidency at the fifth Solvay Physics Conference. This period is now known as the first quantum revolution. The second revolution, in the physics of quantum information, was the subject of the Physics Conference in 2022, 111 years after the very first conference.

The Solvay Conferences were and remain highly regarded by scientists. “Many Nobel Prize winners were regularly invited to participate: Marie Curie, Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Feynman and more recently Gell-Mann, Gross and Englert, to name just a few,” says Rocci. “Many of them have been immortalised in group photos taken in Leopold Park in Brussels.”

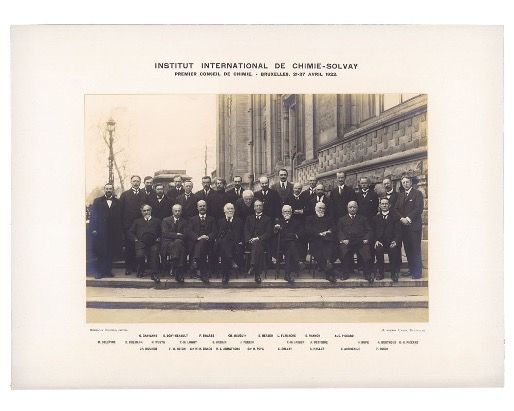

Solvay also established an international institute for chemistry in 1913. In 1922, a second scientific committee began organising the Solvay Chemistry Conferences. Solvay died a month later. “The new conferences first bridged the gap between physics and chemistry, and then between chemistry and other sciences,” says Rocci. “Just like the physics conference, Nobel Prize winners from chemistry came together at the chemistry conferences, where they found a forum to discuss their ground-breaking discoveries, such as the research by Watson and Crick in 1953 on the structure of DNA.”

For Solvay, biology was a domain that merited a conference. He insisted on this, as we know from archival documents from meetings of the International Scientific Committee of the Chemistry Conference. “Until now, nothing came of it,” says Rocci. “There was never sufficient cause to organise it. Now, many experts are convinced that we are at the start of a new revolution in our understanding of the living world, thanks to the converging work of biologists, chemists, physicists, computer scientists and statisticians. They analyse data and build models formulated in mathematical terms. Maths is the essential language shared by all scientific theories. Thanks to that work, fundamental biology can make quantum leaps and possibly open the door to new therapeutic applications for the benefit of humanity.”

The Solvay Institutes aim to be an important player in the development of 21st-century biology, just as they have been for physics and chemistry. The result is the first Solvay Conference for Biology, based on the unique model of the Conferences for Physics and Chemistry. The first conference takes place from 18-20 April and will be chaired by Professor Thomas Lecuit of the Collège de France, director of the Turing Centre for Living Systems. Rocci: “The conference, titled The Organization and Dynamics of Biological Computation, will bring together 35 experts chosen by an international scientific committee. It aims to promote our understanding of how information is transmitted and processed by biological systems, in a multidisciplinary way. Thomas Lecuit’s research on the general question of the origin of forms in biology and the nature of morphogenetic information is a perfect example of transdisciplinarity: important contributions to the understanding of morphogenesis were first proposed by the famed mathematician Alan Turing in 1954 and refined by the biologists Lewis Wolpert and Francis Crick in the 1970s.”

The big guns are being pulled out for the biology conference, including lectures by leading scientists at the public event on 21 April at Flagey. Anthony Hyman, director of the Max Planck Institute in Dresden and winner of the prestigious Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences in 2023, will discuss the physical and chemical mechanisms of information transfer at the cellular level in his lecture The Social Life of a Cell. Stephanie Palmer, professor at the University of Chicago, will give a lecture called Seeing What’s Coming, which explains our brain’s anticipation mechanisms. How does Serena Williams judge the ideal place to receive and return a ball from her opponent, all in a fraction of a second?

Solvay’s journey, the history of the conferences and the International Sovay Institutes are being studied at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) via its participation in the Solvay Science Project, a cooperation between the Brussels universities VUB and ULB. The Solvay Science Project is the basis for dissemination of the history of the conferences and was part of the application to include the Solvay Archives in Unesco’s Memory of the World Register, a recognition that was officially granted last year.

“With the first Solvay Conference for Biology, the Solvay Institutes are continuing a long and impressive tradition,” says VUB rector Jan Danckaert. “Every scientist knows two names: Nobel and Solvay. For more than a century, the Solvay Conferences have been bringing the cream of the world’s scientists to Brussels. I invite anyone who is fascinated by science to Flagey on Sunday for a unique insight into this very important event. You can also explore the history of the Solvay Conferences online via the Solvay Science Project website.”

About the researcher

Alessio Rocci is a postdoctoral fellow at the VUB thanks to the Fund for Natural Sciences in Society, established by alumna Krist’l van Ouytsel. Rocci works with Franklin Lambert, a retired VUB professor and former member of the Solvay Institutes. Lambert has published a book with Frits Berends on the history of the first conferences, called Einstein’s Witches’ Sabbath and the Early Solvay Conferences: The Untold Story. Rocci and Lambert are working on a book about the impact of Solvay’s project on the first quantum revolution.

More info:

Alessio Rocci: +39 349 420 34 60

Jan Danckaert: +32 486 488062